Brand Loyalty

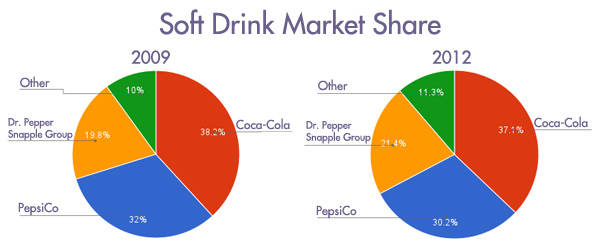

Brand loyalty can run deep. When a consumer decides that they are loyal to a brand, it is very difficult to sway them away to the competition. Take Coke and Pepsi as an example. For years these two companies have fought to maintain their market share with their respective customer loyalty. These two companies have indeed made it into the hearts of American’s and people all over the world. I know people who will pick their restaurants due in large part for the simple fact that the restaurant offers Pepsi over Coke. Other people will note which store has the best deals on Coke and frequent that store over a competitor that offers a higher price for their favorite soft drink. Why do people choose one brand over the other and stick to that decision even more then they stick to many other more important decisions in life?

My theory is that once a person chooses a product that has such high frequency as Coke and Pepsi, their decision gets mapped into their own identity. Once the brand decision has been made, every time they see the brand thereafter, it re-affirms their previous decision and becomes linked to their own identity within the brand recognition event. This makes it very difficult to switch brands because in essence the person would be changing a part of their own identity.

The Pepsi Challenge

An example of a brand campaign imbedding itself into personal choice, identity and loyalty is that of the famous Pepsi Challenge show-down between Pepsi and Coke. Pepsi initiated the challenge in 1975, when it launched the Pepsi Challenge taste test. The tests and subsequent commercials took place in malls and shopping centers where people were asked by a Pepsi representative to do a blind-taste test between two cola drinks — one Pepsi, the other Coke.

The result advertised was that most consumers preferred the taste of Pepsi. The Pepsi Challenge has been featured prominently in much of Pepsi’s TV advertising. Coke later decided to play Pepsi at its own game, when in 2009 it ran a promotion reminiscent of the Pepsi Challenge, trying to persuade consumers that its Vault drink tastes better than its rival’s Mountain Dew.

The taste test became a conversation – one of which we probably all have had at one point or another – voicing our opinion of which Cola we prefer and sometimes with a debate ensuing to back up our personal choice. The taste test challenge struck a cord with people as they followed the campaign, chose a side and drew a line. Their identity intertwined with the product, an era and a marketing brand flavor of their choice. This is a powerful example of brand loyalty at play.

Brand Neural Mapping (BNM)

This theory, called “Brand Neural Mapping”, may help explain why strong brand loyalty occurs. This neural network mapping event happens when a person chooses a brand over the competition and links the choice to their own identity. This neurological theory could be a significant reason why social marketing is so effective. As people are conversing and interacting with friends when they are introduced to a product by a trusted friend they immediately map the friend to the product association in their brains. This neural network association is powerful. Their personal preferences and feelings toward that friend could produce an immediate acceptance for the product before researching or trying the brand themselves. Later, when the person interacts with the product they will often feel so accepting and associated with the product on a personal level that a purchase is highly likely. If, after the product or service is tested and then accepted, the rate of rejection or change to a competitor thereafter is very low.

By comparison, there are two well known traditional brand frequency theories that include Ebbinghaus and Smith respectively.

The first was derived from research conducted by Hermann Ebbinghause in the late 1800’s. His findings concluded with a summary of 20 brand exposures are required to produce an acceptance response from a customer. This theory stipulates that it takes on average 20 times for a person to process a brand in order to invoke a purchase.

His 20 steps are as follows;

The first time people look at any given ad, they don’t even see it.

The second time, they don’t notice it.

The third time, they are aware that it is there.

The fourth time, they have a fleeting sense that they’ve seen it somewhere before.

The fifth time, they actually read the ad.

The sixth time they thumb their nose at it.

The seventh time, they start to get a little irritated with it.

The eighth time, they start to think, “Here’s that confounded ad again.”

The ninth time, they start to wonder if they’re missing out on something.

The tenth time, they ask their friends and neighbors if they’ve tried it.

The eleventh time, they wonder how the company is paying for all these ads.

The twelfth time, they start to think that it must be a good product.

The thirteenth time, they start to feel the product has value.

The fourteenth time, they start to remember wanting a product exactly like this for a long time.

The fifteenth time, they start to yearn for it because they can’t afford to buy it.

The sixteenth time, they accept the fact that they will buy it sometime in the future.

The seventeenth time, they make a note to buy the product.

The eighteenth time, they curse their poverty for not allowing them to buy this terrific product.

The nineteenth time, they count their money very carefully.

The twentieth time prospects see the ad, they buy what is offering.

His conclusion was that if you expose a person enough times to a brand they will eventually move to purchase if the proper opportunity presents itself.

The second theory, outlined by Herbert Krugman, concluded that it takes only three brand exposures for a person to determine their brand decision; curiosity, recognition and decision. This view differs from Ebbinghaus in that after the third exposure the consumer has made their decision and no matter how much frequency they receive thereafter the decision has already been made and will not change.

The BNM theory differs from both of these traditional brand frequency theories in that it gives weight to personalization when a person processes associations and lifestyle messaging. Weight is given to the event when a friend or acquaintance is linked to a product and when a person identifies with a lifestyle message that is then linked to a brand. When either of these occurs the frequency rate is multiplied, resulting in less frequency steps. Applying the BNM model to social networking and taking Ebbinghaus’s model as an example, would look like this;

The first time people are engaged in a conversation in a social network with a friend and a product is discussed or seen in association, the frequency = 5-10 steps in 1 depending on emphasis of product in social scenario.

The second time, they engage with a different friend with the same product = 5 frequency

The third time, they see the product outside of social environment, they feel the product must have value and trust it would be good for them to obtain and start to budget for the amount needed.

The fourth time they are reminded about the product through online ads, print or otherwise they move to purchase.

After purchase they submit review information back to their social network, reinforcing acceptance and creating brand awareness for additional friends in their own network creating an exponential brand frequency effect.

In this respect the rate of brand acceptance is reduced to 4 frequency steps with an exponential growth factor for the 5th step.

Another application of the BNM model is when the product is linked to lifestyle messaging. If the consumer associates positively to the lifestyle being communicated and linked to the product the same 4 step rate of acceptance is applied. These two scenarios often go hand in hand as friends and lifestyle are so intimately integrated.

The best use of applying the BNM model is when providing a quality product or service is a core company objective. In fact, a company with authentic care and integrity for their customers will seek out the core needs of their customers in relation to what they offer and alter their product and services to better serve the customer and community. Communicating the need met, the solution it offers and life improvement benefits in the brand marketing is a win win situation for the customer and the company. Using this BNM production to market method drives the company and brand to consistent improvements and customer growth.

Leave A Comment